Hundreds are feared dead in the Valencia flooding, but the figure is expected to rise dramatically. And anger at the authorities is starting. Catherine Dolan and Eugene Costello report…

The death toll from last Tuesday’s flooding in Valencia officially stands at 211 as of today (3 November). Many fear this will double, triple or quadruple as garages and underground car parks are drained of water, and vehicles searched for corpses.

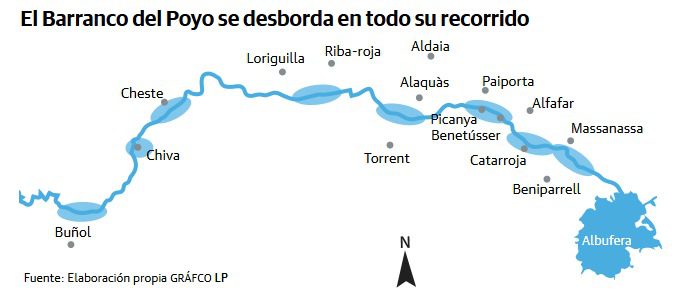

It was an unprecedented event. Tuesday saw a year’s worth of rainfall in just eight hours in some areas, especially higher inland. It was this build-up of water that caused the devastation we’re seeing now. The water furiously barrelled into the Barranco El Poyo, a dry riverbed, which runs from Bunyol in the west. It passes all the towns south of Valencia, bursting its banks along the entire route. This caused the terrible flooding in its wake.

Map showing the Barranco del Poyo which flooded along its whole route.

Why were people not warned about what was to come?

Many blame the regional government. In particular the president, Carlos Mazón of the right-of-centre Partido Popular (PP) now in control of the regional government, the Generalitat, for not sending the civil protection alert out early enough. AEMET, the state meteorological agency, issued its first red alert at 07:31 on Tuesday, but the first civil protection alert to sound on all mobile phones was not heard until 20:00, more than 12 hours later. By this time, homes in towns to the south of Valencia were already a metre or more deep in muddy, brown water. Many believe that lots of lives would have been saved had the alarm been sounded earlier.

Mazón put out a tweet following a press conference at 13:00 on Tuesday, complacently predicting that the storm would have passed by 18:00. That was when the worst of the flooding hit and devastated towns across the Valencian community. He later deleted the tweet but it speaks to a blasé and complacent attitude and not taking it seriously that in the event cost many lives.

Bernadette Maria Campbell Harris told Valencia Life: “Compared to most and even though we live on the brow of the Serra Calderon mountains we have been lucky as the hill helped a lot with the flow of water.

“All I am convinced of is that the warning should have gone out a lot earlier. I tried taking my dogs out for their usual walk at 6pm and that was the point it changed for the worst. Thunderstorms and lightning were coming together. We rushed back to the house.

“I’ve never been so scared and you can imagine coming from Ireland and its weather events, that’s saying something.”

During the afternoon and evening of Tuesday, hundreds of people found themselves trapped in cars on motorways that had turned into gushing rivers in a matter of minutes. Others, unable to make the journey home were forced to stay in warehouses and offices. At Bonaire, staff, who hadn’t been allowed to go home, as no alert had sounded, were also trapped and spent the night on the roof or in the cinema.

A still-unknown number never made it home as their cars were thrown around in the water or they became trapped in underground car parks or lifts as the water gushed in around them. Officially there are 211 dead, but it is feared that number could reach several hundred or even 1,000.

Hellish journey for British family

Mike McDowall, 56, who lives with his wife George, 49, and daughters, Molly, 12, and Martha, 8, in Xativa, around an hour south of Valencia, set off in his car on Tuesday evening. They were on a mission to rendez-vous with a lorry delivering rescue puppies around Spain and were due to meet at Torrent.

Says Mike: “We set off late afternoon but on the journey along the A7, the storm hit. We were unable to reach Torrent. Eventually, we had to give up and turn back. By now, the main road was becoming waterlogged and we had to drive very slowly, taking the CV-50 from l’Alcudia towards Alzira. We stopped at a lorry park where the drivers had got out of their vehicles and were waiting for the water to subside. In the morning, we saw that one had been reported as missing with his lorry abandoned by the roadside where we had been chatting to them.

“On the main road, the CV-50, there were very few cars, but the only one ahead of us suddenly disappeared into deeper water and its lights went out. I slammed on the brakes and reversed up the dual carriageway for about a mile and then drove the wrong way around roundabouts to avoid deep water, taking to dangerous, flooded cross-country roads. We finally made it home about 4am. It was truly terrifying.”

While many struggled for their lives, those who still had internet connection, watched with horror as the devastation unfolded before their eyes; vehicles tossed around like toy cars, bridges such as that at Picanya, just a few kilometres outside of the city, destroyed in seconds, people clinging onto palm trees and lampposts for dear life, some winning the battle, others washed away.

Horrendous stories emerged, such as that of Lourdes María García Martín, a mother with a three-month old baby who tried to take refuge on the roof of a car in l’Alcudia. At around 20:30pm she reportedly sent a text to a friend saying the waters were rising and to please look after her other two children before she and the baby were washed away to their deaths.

Reports also emerged of an old people’s home where elderly residents were sitting down to eat at the time the floods hit. Heartbreakingly, neighbours later recovered five bodies.

A late and uncoordinated response

On Wednesday morning most schools and universities across the province were cancelled, but a few still opened and some people still went to work. Others worked from home, some complaining that they were having trouble with their internet connection. Those in the unflooded areas began to understand the extent of the disaster that had befallen their neighbours across the river as photos and videos circulated on social media.

By the light of day on Wednesday morning, residents in the towns south of Valencia started to see the full horror of the devastation from the night before, rubbish bins upturned, cars left piled on top of each other by the force of the water. There was no water, no electricity. Between 150,000 and 250,000 homes were reported to be without either or both. Residents able to send messages from inside the affected areas described the scenes as “catastrophic”, “apocalyptic”.

There were reports of a body found as far afield as El Mareny de Barraquetes, a village between El Perellonet and Cullera south of the rice fields and lagoon of Albufera. This was a victim of the turbulent waters, washed out to sea.

While they tried to digest the gravity of their surroundings, the people of Paiporta, Benetusser and the other towns destroyed by the floodwaters believed that help would be on its way, that the emergency services would soon be coming to clear their streets of the detritus, as they began the long, painful task of throwing away cherished items ruined by the flood and clearing out the thick, sticky mud from the ground floors of buildings.

But the emergency services didn’t come, nor did the police, nor did the army.

Just an army of tractors, from towns like Cullera in the south, and Bétera in the north answered the call to come and start clearing the streets.

https://x.com/plburjassot/status/1852440788057362838t=sB3I4oWRgIzwfKuzKakAvw&s=0https://www.facebook.com/reel/1645303669720938

The answer to this disaster has been the people. On Sunday, reports emerged of the people throwing mud at King Felipe VI and Carlos Mazón who were visiting disaster-struck towns. They were shouting, “Asesinos! Asesinos!” (murderers) at the pair, who were ringed and protected by police. Despite prime minister Pedro Sánchez announcing that thousands of troops would be sent to help, many are claiming that there has been little evidence of them on the ground. One witness told Valencia Life, “Mazón is the villain. At least the king stayed to face the anger of the protestors.”

On Thursday, with the lack of any coordinated, official response hundreds of thousands of volunteers armed with brooms, shovels and wellie boots, made their way to the affected towns south of the city, This was mostly on foot as the roads were blocked or cut off to traffic to allow emergency vehicles through. These volunteers worked at clearing the streets as much as they could, helping residents clean the endless mud from their houses, all the time with no electricity or water, bringing with them as much as they could carry in terms of cleaning products and food. People took items to friends stranded there: water, bread, wet wipes, dry shampo

Tournarem: Volunteers in Paiporta take a break from clearing mud to join in the Hymno de Valencia (source: Valencia Secreta)

A group of French firefighters arrived at the scene without official permission to access, determined to help. They reported being shocked when residents told them they were the first help they’d seen. Meanwhile, offers of help from firefighters in other parts of Spain had been turned down.

Firefighters from Bilbao ready and willing to come to Valencia since Wednesday have not been called.

On Thursday Sergio, a teacher from Catarroja, was finally able to contact his fellow teachers to let them know he was safe. He sent a message saying: “It’s like a scene from a disaster film, where there’s nobody around, people stealing, piles of rubbish uncollected, everything covered in mud, absolute chaos.”

In towns across the region supermarkets were left bare as people bought up essential items to send to the affected towns. Collection centres were set up like this one in Levante stadium and piled high with donations of items such as nappies, toilet rolls, milk, water, baby food, cleaning products.

Friday arrived and the stream of Valencians wanting to help became a river, even though the regional government told volunteers not to come, to keep the roads clear, to let the emergency services through. This was despite reports of any emergency vehicles in attendance.

By now volunteers were being advised to wear face masks, gloves, long trousers and wellie boots. The water, which contained human and animal corpses, had been stagnant for three days and the risk of disease was becoming a serious threat.

In an attempt to organise the volunteers, from Saturday morning the authorities put on 50 buses to take helpers from the city of arts and sciences to the affected towns. Volunteers had to meet at 7am but by 1pm many buses had only reached Bonaire shopping centre from where they were to be taken to different areas to work. On the first morning an estimated 15,000 volunteers turned up at the City of Arts and Sciences for those 50 buses. Fortunately, many ignored the instructions to take a bus and went on foot.

But still the emergency services didn’t appear in many places, despite the huge photo of a group of soldiers printed in The Guardian on Saturday. It seems the government wanted to give a good solid image to the outside world but it was at odds with local reports by volunteers..

On Sunday, when finally more emergency services from other parts of Spain could be seen on the ground, the order came once again for volunteers to stay away. They didn’t. The stream of volunteers once again crossed the river. Manuel, a 19-year-old law student, who had made the journey on foot with his friends every day since Thursday decided to take a taxi to the affected area. The taxi driver refused to accept payment.

Why was the government response so delayed?

The autonomous regional government in Valencia is the right-wing PP (Partido Popular), which is responsible for what has happened so far, the barrancos that haven’t been cleared, for not sounding the alarm which resulted in so many deaths. The socialist national government didnt want to declare the state of alarm because then they would be responsible for all the post-catastrophe management, the possibly 2,000 deaths and however many hundreds of thousands of injured people. Not to mention the thousands of homes and small businesses including restaurants, cafeterias and so on.

One source told Valencia Life: “The PSOE will be thinking, let the PP and the Valencian government deal with that, it’s their problem. This is why the help hassn’t been arriving, why individuals are having to bring their own tools, they’re not being provided with gloves or facemasks…. These are the same ones who sent out the alert too late, which caused many of these avoidable deaths.”

We need all the organisations, NGOs

Chronicle of the DANA event

AEMET, the state meteorological agency, issues a red alert at 07.31 for the whole Valencia province. At 07.42 another alert was issued for the south of the province and at 09.48 a further alert was sent out for the north of the province. Red indicates “extreme weather risk” and recommends residents to “not travel unless extremely necessary.”

During the morning many municipalities advised parents to come and collect their children from school from lunchtime onwards to avoid the rain expected later.

At 13.00 Valencian president, Carlos Mazón (PP), gave a press conference at which he assured people that the storm was moving towards the Serranía de Cuenca and that by around 18:00 it would ease up over the rest of the Valencia region.

By 15:00 ground floors in the town of Utiel were completely flooded and the Valencia government raised the alert to Level Two in Utiel, Requena and La Plana

On Wednesday morning the rescue operation should have begun in earnest, but again many say the organisation of the government has been lamentable with still no emergency services having been seen in many villages days later.

What is a DANA?

The exceptionally heavy rainfall, known as a DANA (short for the Spanish Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos) occurs when a mass of cold air in the atmosphere comes into contact with warm air close to the ground, creating instability and causing heavy storm clouds to form. DANAs are not unusual in the Mediterranean in the months of September, October and November, but their erratic movement makes them more difficult to predict, and the presence of a DANA doesn’t always mean there will be heavy storms. ¿Qué significa realmente una DANA? | RTVE

The term DANA is now being used by meteorologists instead of the term Gota Fria (cold drop) which they traditionally used for the storms at the end of summer.