Valencia’s DANAs explained. In stark comparison to the chaos surrounding the DANA at the end of October, which was a complete lack of preparedness, mismanagement and catastrophe, this week we saw alerts with schools closed and non-urgent hospital visits cancelled. Catherine Dolan looks into what is behind the Valencia flooding…

You might be asking yourself: What just happened this week? Was it really necessary to close the schools for three whole days? Did my doctor’s appointment really have to be postponed? All this disruption for a few drops of rain?

And yes, that is an understandable reaction, but here in Valencia the danger is not only from heavy torrential rain where you are, it’s also about rainfall inland which has to somehow make its way to the coast. Heavy rainfall was forecast and until it falls, it’s difficult to predict exactly where that water will arrive. And after the catastrophic management of the floods in October, the authorities seem to have decided to err on the side of caution.

Weather events

The weather this week was another DANA, also known as a gota fría or cold drop. This is a meteorological phenomenon caused when a mass of cold air at a high altitude becomes completely detached from a cold current and descends over another current of warmer air. It is literally an isolated depression at high levels in Spanish Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altas, hence the name DANA. This is usually a pocket of polar air that gets cut off and mixes with the warm, damp air above the Mediterranean. These events commonly occur in the autumn when the Mediterranean has had the whole summer to warm up.

However, as a result of climate change, not only are these weather events happening at other times of the year, but we have also seen the Mediterranean reach record temperatures in the past few summers, making these autumn storms even more intense.

Built on an alluvial plain

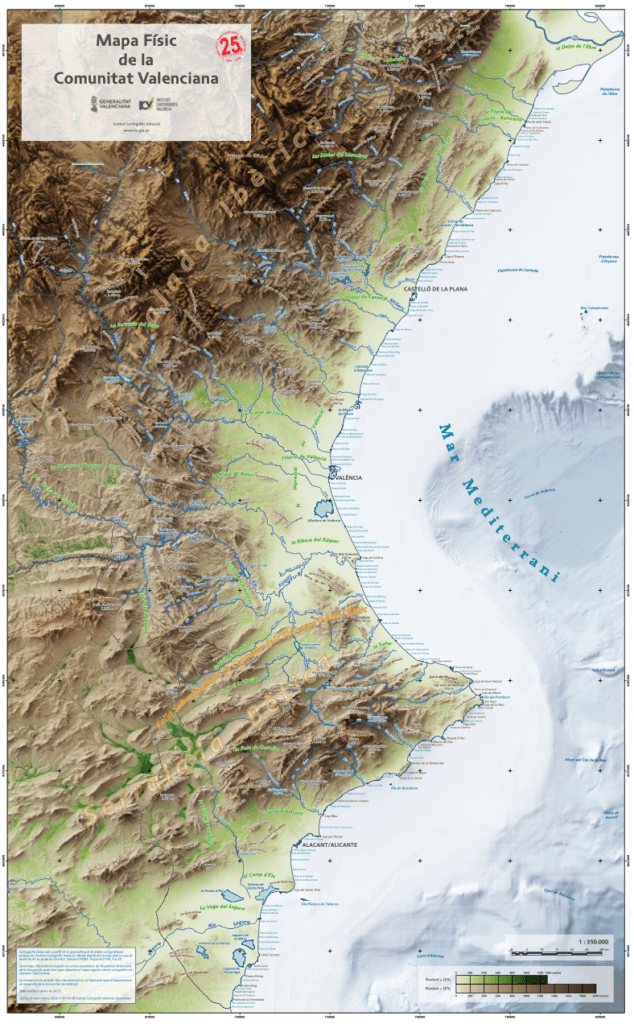

If we look at the relief map of the area around Valencia, we see hills and mountains to the north and west.

These mountainous areas of the Mediterranean countryside are filled with many dry riverbeds, sometimes called barrancos, or ramblas, which spend most of the year completely empty or at most with a small trickle of water running through them. But when it rains these empty ravines become extremely dangerous as they fill with fast-flowing water.

Let’s not forget that Spain is the second most mountainous country in Europe, after Switzerland, and when humid air from the sea is blocked from going further inland, it is pushed up these mountains, the air cools, condenses and rapidly falls as rain which causes torrents of water that can flood low-lying areas.

Returning to the map, we can surmise that if it rains in the Sierra de Calderona, to the north, the channels of water will feed into the Barranco de Carraixet which, if it burst its banks, could cause flooding in towns to the north of the city. Talk to older residents of towns like Tavernes Blanques and they will tell you tales of pigs floating in the floodwaters. Likewise, if the heavy rain falls in the mountains to the west or south, this will fill the Magro River or the Barranco del Poyo, as we saw in October with devastating consequences. Finally, rain in the mountains of La Serranía, to the northwest, would feed into the Turia River.

Historic flooding

From the map we can also appreciate just how flat the land around the city of Valencia is. The city and its surrounding towns are built on an alluvial plain, a flat area resulting from centuries of rivers depositing sediment in their floodwaters. Being fertile soil, the area became perfect for farming, hence the areas being called l’horta nord and l’horta sud.

The whole area is prone to flooding, indeed has flooded on and off for centuries, which the farmers who worked the fields there learnt to live with and the large towns we find there now were just small villages.

Until last year, the most significant flooding in recent memory was the Riada of 1957. On the 14 October 1957 the Turia river burst its banks, and the city of Valencia was devastated by flooding which caused the deaths of at least 81 people and substantial damage to property. As a result, the Plan Sur, was carried out in the 1960s and early 70s to divert the river from its original course through the city to a newly excavated riverbed to the south, which could transport 5,000 cubic metres of water per second. This massive piece of engineering protected the city but did nothing to protect the towns to the south, where over the past 20 to 30 years there has been intensive building, with very little thought as to what would happen if the area flooded, as happened on 29 October last year.

With so much construction of impervious surfaces, like roads, housing, shopping centres and industrial estates, there is less area of ground that can absorb water, meaning the water pools on the surface. In addition, the natural ridge formed nearer the coast means water cannot reach the sea so easily.

What was planned for the area south of Valencia?

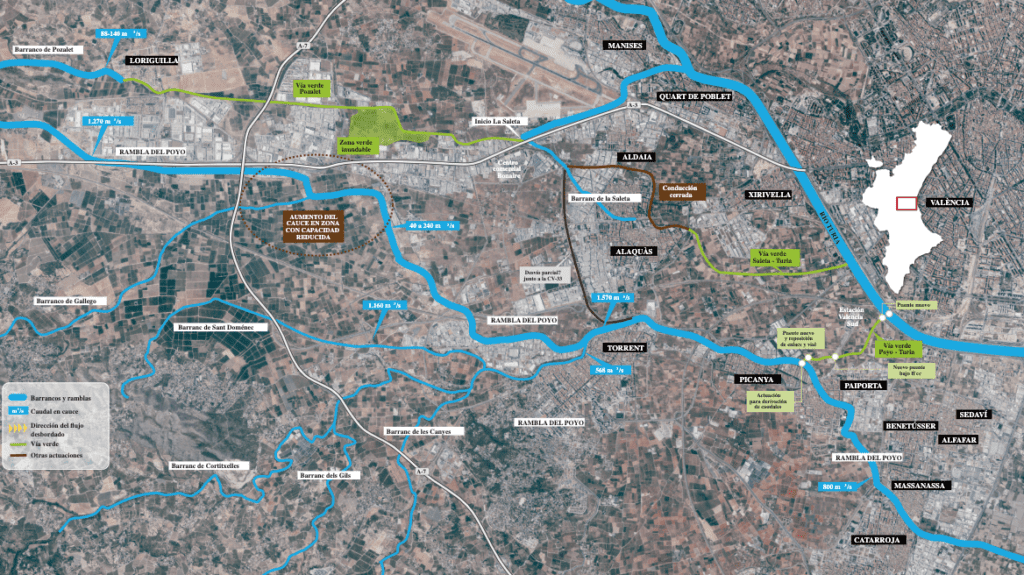

While the city was protected with the river being redirected, plans, costing around 150 million euros, were made for the areas to the south of Valencia, However, they were largely not carried out. Experts now believe that, while these projects might not have prevented the devastating floods of last October, they would certainly have gone a long way to lessening the outcome and saving lives.

In the 1990s a plan to build a dam in Cheste and carry out traditional channelling of the barranco as far as the Albufera was stopped by the European Union on environmental grounds, as it was believed it would have caused the silting up of the lake, a natural treasure in the region.

The only work actually done was the channelling of the barranco del Poyo at the end of its trajectory, from Paiporta to Massanassa and Catarroja.

Among the plans, dating back to 2006, were different actions along the course of the barranco; reforestation and microdams further upriver to protect against erosion at the headwaters, designated floodable areas lower down in the floodplain as well as green corridors, or Via Verdes, joining the Poyo with the new Turia riverbed, which would ease pressure on the narrower barranco which runs through towns. Having seen the level of water in the new Turia riverbed last October there are some who argue that this riverbed wouldn’t have room to accommodate extra water from the Poyo, and that might be true. However, others say that the chances of the high water point of both the Turía and the Poyo coinciding exactly wouldn’t be that high and that there might be enough room for the Turía to lend a helping hand to the Poyo.

How is climate change affecting these events?

As we mentioned before, the record temperatures of the Mediterranean waters in summer have increased the intensity of the autumn storms. The hotter summers also mean drier soil, which is less able to soak up water, causing flash flooding

Rising sea levels from climate change made it more difficult for the floodwaters to go out to sea, and some scientists also suggest that climate change may have caused the storm to move more slowly, creating more rainfall in the same place.

Global warming also means that the DANA phenomena will not only be restricted to the autumn but could occur any time of the year.

What can be done to prevent more disasters in the future?

That is the 64 million dollar question While many don’t doubt the negligence of Mazón in dealing with the last DANA, there should arguably be less energy spent calling for his resignation and more spent on looking for ways to avoid future disasters. A good starting point would be a cross-party consensus on consulting with environmental and infrastructure experts to look at ways in which the more savage effects of DANAs might lead to a lower cost to protect human life and property. We cannot again experience what the region had to endure in October.